This story was originally published on Medium by The Development Set.

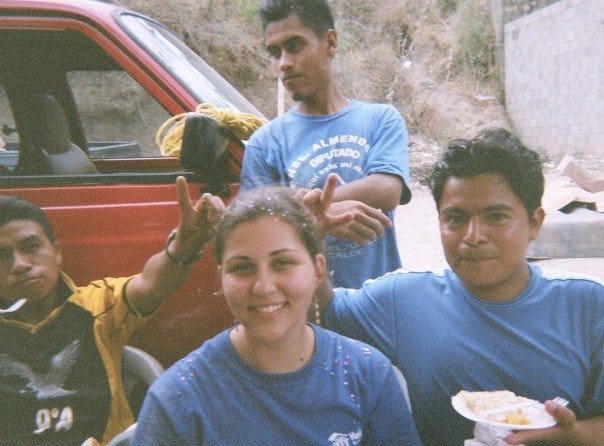

I recently came across a grainy photo of myself from a Habitat for Humanity trip to El Salvador nine years ago. I’m grinning in a plastic chair a few feet from our work site, oblivious that two local masons are making bull horns — El Salvador’s answer to bunny ears — above my head. My hair is sprinkled with rainbow-colored confetti, the innards of a Patrick Star piñata. I’m full of cake and soda enjoyed under the jealous gaze of an itinerant goat and dog. It isn’t exactly the image of hard labor in the name of sheltering the needy.

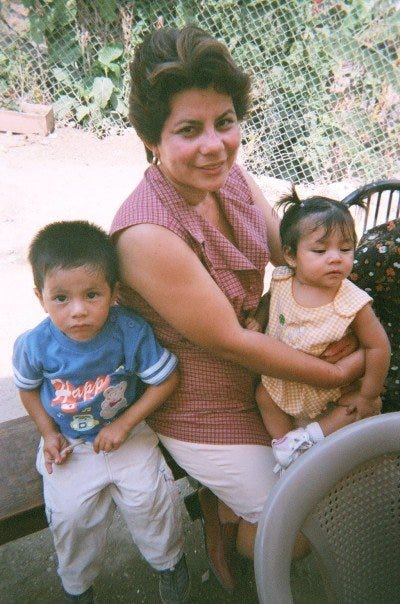

The afternoon fiesta came courtesy of two families for whom my team of college students was helping build houses. I spent the most time with the Ovandos: Alberto, who shuttled us around in his red van; Magdalena, a teacher with neatly coiffed short hair; six-year-old Fatima, in her pressed school uniform; Daniel, the shy toddler; and baby Rebeca.

During my week in El Salvador, I hauled bricks, mix cement and spread mortar under the hot sun. I also danced to reggaeton in a San Salvador bar, spent a night at a beachfront resort, and visited local tourist sites with Alberto playing chauffeur and tour guide.

Looking back at the photo, I wondered: Was I actually doing good or just having fun?

The question matters because two million people volunteer with Habitat each year. The charitable behemoth, whose 40th anniversary is this year, says it has helped nearly seven million people in more than 70 countries, mostly by improving their housing. This includes building new homes, repairing existing ones, providing design services, and supplying financing.

For volunteers who build far from home, as I did, Habitat is a sizable segment of the “voluntourism” trend, now estimated to be a $2 billion global market. In the fiscal year through June 2015, nearly 13,000 Habitat participants went abroad to volunteer.

During the winter of my senior year in college, I wrote letters to family friends and sold donated textbooks on Amazon to fundraise for the El Salvador trip. Besides the allure of foreign travel, I thought I’d be making a dent in housing inequality in the developing world. I’d gotten interested in housing rights after spending a few years volunteering for a student-run legal advice hotline and a summer advising tenants at a legal aid organization. Just as I’d helped clients navigate U.S. courts, I assumed I would make a tangible difference abroad.

In April, I left a dark, snowy Boston with 11 classmates I didn’t know. We landed in Panchimalco, a small town half an hour from the capital that’s home to one of the country’s largest indigenous populations. It was a place of short palm fronds and cobbled streets, centered around a white church that looked as if it had been carved from a bar of soap.

Dating back to 1725, the church was the oldest colonial structure to withstand El Salvador’s ruinous earthquakes. The latest major quake in 2001 had damaged nearly 272,000 homes. In 2012, over half of El Salvadorian households lacked access to adequate housing, according to the Inter-American Development Bank. In Panchimalco, many families lived in homes of tin or mud brick, some with dirt floors. Most grew beans and corn to survive or worked as day laborers.

When my group arrived, we hadn’t learned much of the Ovandos’ back story. Magdalena, then 33, taught at a parochial school in town, and Alberto worked odd jobs as a construction laborer and driver. Every morning, Alberto picked us up and took us to the site of his future house, five blocks from Panchimalco’s church. When we showed up, it had a foundation and low cinderblock wall. We took directions from Habitat’s masons: Jorge, slim and quiet with a faint goatee, and Marvin, petite and always smirking.

My construction skills were nonexistent, but I did what I was told, sporting my worst jeans, a cobalt blue Habitat T-shirt, and a San Francisco Giants cap. I lugged around cinder blocks and dirt, used a huge shovel to keep cement wet, and twisted wire around metal rods.

It sounds like drudgery, but it was a blast to spend the day being active outdoors, joking with my classmates and the masons. Magdalena and the two youngest children often stopped by to chat. We also spent time with the Ovandos during afternoon outings to local vistas. By the end of our five days of work, the wall had grown a bit taller.

I didn’t doubt that I’d had an impact as I flew back with sore limbs and memories of the thank-you party the families threw. Soon the trip became a satisfying line on my resume. As years passed, the experience remained one of the most fun weeks of my life. But I started to question whether it was truly time and money well spent.

Surely local masons could’ve done the work more efficiently. We could’ve sent all the cash we raised instead of leaving a small donation and using most of it for our plane tickets and accommodations. I’d read enough academic papers about neocolonialism to feel slightly uncomfortable with Habitat’s overtly Christian mission and global deployment of Western volunteers to “help” the locals.

Last month, nearly a decade after my trip, I decided to get in touch with the Ovando family. I wanted to ask if I’d had any impact on their lives. I emailed Habitat’s El Salvador affiliate, and Erica Olson, an American who works as the international donor relations officer, contacted the family.

Early one morning, I called the office on Skype. There was Alberto, with the same slicked-back hair and gentle grin, sitting on a blue plastic chair in the Habitat office. He wore a white top with two rows of black buttons, the uniform for his current job as a cook at Olive Garden. He claimed to remember me, even though I’m sure I looked older and decidedly less sweaty sitting in my dining room. Erica translated, and Habitat’s loans officer Marden Garcia also chimed in.

I asked Alberto to fill me in on his family’s story. He explained that when we came, the five members of the Ovando family had been crammed in a one-room house with Alberto’s mother and brother. They owned a plot of land but couldn’t afford to build their own house. With Alberto’s lack of formal employment and 40% interest rates, a bank loan was impossible. Private lenders charged even more.

A colleague at Magdalena’s school told her about Habitat. They fit the affiliate’s criteria because they needed housing and made less than $1,300 a month. Habitat offered to front $6,000 worth of materials and labor to build a modest home with two bedrooms, a common room, a kitchen and a bathroom. It only charged 7% interest with $50 monthly payments.

Alberto was clear that Habitat had changed his life. “It helped us a lot,” he said in Spanish. “It was impossible to get a loan, and Habitat opened the door for us.”

Granted, Alberto had reason to downplay any negatives in the presence of two Habitat staffers and a former volunteer. Yet the process clearly benefited him. He and his wife still live in the house and paid off the debt in less than a decade (the typical period was 13–15 years, Marden said). Just last month, they got another loan from Habitat to expand the house so their growing children can have their own rooms.

But did we actually help with construction?

Alberto said they had worked with two student contingents, ours and a younger group from Oregon. Our manpower helped speed up the process and cut costs, he said, even just moving materials to the site. Still, the house took six weeks to build — no faster than average. I wasn’t convinced that Jorge, Marvin, and local laborers couldn’t have done it faster if we’d just sent a donation and they hadn’t taken time to show us how to put one brick on top of another.

“I had a great time on my trip — I had a lot of fun,” I told Alberto. “But I had literally never moved a brick before. So what was the benefit of having people like me come? Or were there any drawbacks, being honest?”

Alberto’s eyes got bright, and his arms got more animated. “It was a special experience, and I have not forgotten it, spending time with you. It’s not a common experience, but it happened, and we’ll always remember it.”

He said the family still had the T-shirts we’d given them and a Bible we’d signed (apparently I’d blocked that gift out of my memory). I knew first-hand that the house didn’t have tons of storage space, so that was a compliment.

Before we hung up, I asked about the biggest impact Habitat had on his life. He mentioned the loan again. Then our visit.

It’s hard for me to accept that I spent a week volunteering without achieving all that much — that it was mostly about fun and human connections. If you’re measuring development by the numbers, I know we would’ve made more impact sending a check. But I doubt we would’ve fundraised in the first place without the goal of making the trip. And the fun I had was qualitatively different from that of, say, getting hammered in Cancun.

The memories of that week are part of the house’s story and part of my story. It’s not that it led to a light-bulb epiphany. But meeting the Ovandos and seeing the way they lived deepened my perspective as I went to India after college to work in slums, as I debated housing policy in grad school, and as I eventually became a journalist who often writes about vulnerable people. My classmates from the trip went on to medicine, law, academia and the foreign service, and I’m confident that week away from the classroom made them better professionals and humans.

On its website, Habitat’s Global Village program, the division that sends participants abroad, promises that volunteers will be “making the world a better place.”

A humbler approach is in order. The key, I think, is not to go in expecting to be a savior in a hardhat, but rather to share in the lives of people a world away. That connection only deepens if you go in expecting to receive as much as you give.

Una aventura muy bonita, Alberto called our visit. A very nice adventure.

Photographs courtesy of Katia Savchuk. The Development Set is made possible by funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We retain editorial independence. // The Creative Commons license applies only to the text of this article. All rights are reserved in the images. If you’d like to reproduce the text for noncommercial purposes, please contact us.

Read Ethical Traveler's Reprint Policy.