Last year, as we prepared to leave Bangkok for Rangoon, my girlfriend Bo contemplated bringing her rollable luggage. My foster daughter – who is from Burma but was then living in Thailand—laughed. “You can’t roll your luggage in Burma—the sidewalks are too broken!”

That’s not the only thing broken in Burma, I thought to myself. Everything from apartment buildings to taxi cabs seems to be half fallen apart and barely patched together.

That was then; this is now. Burma appears to be on the mend. The differences between a visit in January of 2011 and one in January of 2012 were in many ways like night and day. During this year’s visit, on at least one occasion, we rode in a brand new taxi. While the norm for taxis is still torn seats, broken door handles, and a dashboard full of gaping holes, finding yourself in a new car in Burma was previously unheard of for the casual visitor.

Further, during our recent visit, in Rangoon’s bustling downtown, many stretches of road and sidewalk were in the process of being redone—seemingly for the first time in decades.

But the changes were more significant than the condition of the taxis and the roads. On a personal level, my foster daughter had been able to return home after 4-1/2 years in exile in Thailand. When we visited Burma last year, it broke our hearts that she couldn’t go with us. She missed her mom and her beloved Mandalay terribly. †Thailand had offered refuge but all in all had not been particularly kind.

My personal connection aside, no one could have foreseen the exponential rate of positive change that has followed elections held in Burma in November 2010. The elections (and the accompanying new constitution) were widely considered a sham, rigged in favor of the military-dictatorship. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s party didn’t even participate—the opposition leader herself was still under house arrest. By no coincidence, Daw Suu was released only after the elections had been held, and the predetermined outcome—a landslide for the junta party—had been decided.

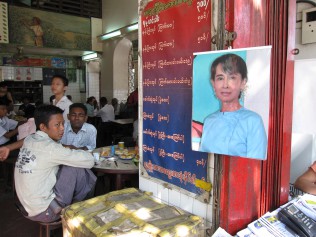

It was less than two months after Daw Suu’s release when we made our January 2011 visit. At that time, the atmosphere at NLD (National League for Democracy – Daw Suu’s party) headquarters in Rangoon was stilted – paranoia seemed to take hold of everyone who entered. Across the street, junta informers kept tabs on everyone who came and went.

On that visit we initially avoided entering the offices – this despite staying for several nights at a hotel just across the street. We walked past several times and I would sneak looks, feeling a strong desire to venture in. I had to resist the temptation, however, because entering would have put our plans at risk. †We were scheming to meet with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi herself at the end of our trip.

Eventually that time came, and we were in the big room downstairs at NLD HQ. Pictures of Daw Suu and Ché Guevara looked down at us from the walls. With our appointed cameraman a no-show, we had an urgent need to use a phone. I was told there weren’t any. When I asked about using a public phone I was told it was not a good idea, as all phones in the area were tapped.

Fast-forward to January 2012. NLD headquarters is a beehive of activity and optimism. People come and go freely and linger out front, in full view of the spies who may or may not still be watching from across the way. The NLD has recently registered for elections, and Daw Suu herself is running for a seat in parliament. A training session for NLD youth is underway in the big room at street level. T-shirts and calendars with Daw Suu’s picture are for sale, and tickets are being sold for an upcoming NLD concert/fundraiser.

My foster daughter met us in Rangoon, and after a few days there we travelled north together by car. In Mandalay, her mom hosted us for dinner. On another night we dined out with her mentor—the founder of an English language school and a master of Burmese puppetry. The previous year we had avoided meeting with either of them, as doing so could have put them at risk with the authorities. One year later, such concerns had evaporated.

In March 2011, Thein Sein—a former general who had swapped his uniform for civilian garb, and run for office—was installed as the President of Burma. At first, no one thought this would have any impact on the dreadful state of human rights in the country. But in October, a remarkable thing happened. The Burmese government suspended a major dam project financed by the Chinese. It appeared they’d conceded to public pressure—something unheard of in a country where tyrannical rulers seemed to operate according to their own whims.

The following month, President Obama announced that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton would make an official visit to Burma: the first visit of a top-level American official in more than 50 years. At the same time, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi registered the NLD to participate in upcoming by-elections. The Lady herself would run for parliament.

When Clinton arrived in early December she spent equal time with President Thein Sein in the capital city of Naypyidaw, and with Daw Suu in Rangoon. When we arrived in Rangoon a few weeks later, pictures of the two women together were a common sight—in the newly liberalized press, and in calendars being sold openly on the streets.

Other visits followed: foreign ministers from Japan, the UK, and France. US Senators came next. Mitch McConnell, John McCain, Joe Lieberman; they all met with Daw Suu, as well as with the President. All of these meetings occurred within the few weeks we were in Burma.

Back at NLD headquarters, I met a video journalist from a French TV station. He had been let into the country with all his equipment: big video cameras that exposed his profession and the reason for his visit. And on the TV in our Mandalay hotel room we watched as Rachel Harvey reported openly from the streets of Rangoon—this following years of filing voice-over reports from her base in Bangkok.

Even George Soros visited the country while we were there. Soros—whose foundations have supported the democracy movement in Burma for 20 years—met with Daw Suu not once, but twice—both before and after meeting with the President.

All of this paled in comparison with what came next. On January 12, 2012, after more than six decades of ongoing war, the Burmese Government and the Karen National Union reached an agreement to establish a ceasefire. The following day, 300 political prisoners were released, including leaders of the 1988 student protest movement and the 2007 uprising known as the Saffron Revolution. That same day, the US Government announced it was moving to restore full diplomatic relations with Burma.

Is all this heady change enough? Absolutely not. Many political prisoners remain behind bars, and those released were not released unconditionally. Fighting rages on in the northern region of Kachin state.

Collectively though the changes of the past year constitute a paradigm shift, past the point of no return. The feelings of optimism can be felt on the streets of Burmese cities. While some of the individuals I spoke with remain skeptical, the majority are feeling an undreamed of optimism.

After decades of repression and economic mismanagement, Burma is in need of a lot more mending—and not just the city streets and sidewalks, but all government institutions and civil society as well. I’m wondering if many of Burma’s best and brightest who were forced into exile will return to help rebuild their country. They will be needed.

And as Burma opens up further to tourism, volunteerism, and outside investment from the west, what impact will these changes have on the country and its rich culture?

On the first point—tourism—in 2011 there were about 400,000 foreign visitors, mostly from China and Thailand. Europeans were far down the list, and Americans down even further. As Burma’s image in the west improves, the percentages will shift, and the total number will skyrocket. (Neighboring Thailand, in comparison, had over 14 million foreign visitors in 2011.)

The “go or don’t go” debate amongst conscientious travelers is a thing of the past. The question now is how to best use travel as a vehicle for cultivating new friendships and supporting positive change. †The opportunities are vast.

As part of our recently released Ethical Destinations 2012 report, Ethical Traveler cited Burma as a “Destination of Interest.” While far from being a candidate for the Ethical Destinations list, the fact that Burma was mentioned in a positive light in the context of travel is remarkable.

Now ET—in partnership with Global Exchange Reality Tours—is in the early stages of planning an “Ethical Journey” to Burma for later this year. As the country continues to liberalize, there’s never been a better time to go.

Whether you go on your own, or as part of a socially conscious tour group, go lightly. As has been said, “tourism is like fire—you can cook with it, or it can burn down your house.”

###

For those considering a visit to Burma, an excellent resource for the mindful traveler is Tourism Transparency – http://www.tourismtransparency.org.

For detailed information on political prisoners in Burma, refer to the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma) – http://www.aappb.org. And if you’re in the US, note that the AAPP’s founder/director, Bo Kyi, will be undertaking a month-long speaking tour in the US starting March 10, 2012 in Oakland, CA. The new film, “Into the Current”—by Jeanne Hallacy, and featuring Bo Kyi—will be screened at many of the tour events. Contact gregg@ethicaltraveler.org for more info.

Read Ethical Traveler's Reprint Policy.