“In a real revolution, you either win or die.”

– Ernesto “Ché” Guevara (who managed to do both)

I was twelve years old when Ché Guevara was shot by a firing squad in Bolivia. That was in October, 1967. The Argentina-born Guevara had left Cuba, and was fomenting revolution among Bolivia’s farmers. He was ambushed, brought in by the Bolivian Army, and shot. The final order to carry out the execution may have come from President Richard Nixon himself.

Since I was a teenager, Ché has been the world’s most recognizable icon of grass-roots revolution. In the city of Santa Clara, which lies almost at the center of Cuba, he’s practically a god. During the last days of 1958, Ché’s guerrilla forces blew up a supply train and liberated this town. It was the coup de grace that sent Batista on the run, and cleared the way for Castro’s regime to step up.

At first, the images of Dr. Ernesto Guevara on billboards and buildings all over the country are a novel, even inspiring sight. But it’s possible to get a little tired of him. I’ll go further. It’s possible to become rather cynical about the way this brilliant, fanatical and intensely charismatic rebel has been canonized in the service of socialist propaganda. Not much is known—or said—about the friction between Fidel and Ché during the six years after the taking of Santa Clara. But it’s evident that, no matter what victories he may have achieved abroad, he was worth his weight in gold as a martyr.

When heroes die young, they stay young forever. Exploring Santa Clara’s Complejo Escultorico Memorial Comandante Ernesto Ché Guevara, I was immediately struck by a similarity to the cultish obsessions surrounding James Dean or Jim Morrison. Politically, of course, he had less in common with those entertainers than with figures like Bobby Kennedy or Martin Luther King Jr. (though both men would spin in their grave to hear me say that). But as a youthful, long-haired, dashing and athletic rebel—who literally wrote the book on guerrilla warfare—Ché really has no peer.

Despite my cynicism, it was mind-bending to realize what a fantastic-looking guy he was in medical training (he bore a slight resemblance to the young Sean Connery); to learn that he edited his college rugby magazine (Tackle), and to see a photo of him smoking a cigar and reading Goethe in his combat fatigues. Or to crouch down in front of a polished vitrine, at eye-level with his famous beret, its five-pointed star gleaming against black velvet.

Not everyone, however, is equally happy with La Revolucion. We were shielded from that reality during our group tour, for what are perhaps obvious reasons. But exploring a bit of Cuba on my own, I’ve met people who—though they accept the reality of their lives—find ways to express their wish that things were otherwise. The English teacher who asks only that the government “let people live their lives, because we only have one life to live.” Or the elderly owner of a casa particular whose family of doctors and lawyers—immigrants from Spain and France—lost their homes and land when Castro nationalized property. Or the guide whose single wish is to see his sister in Tampa, to touch her arm, before he dies. And there is so very much more we don’t hear, because people do not speak this way.

I’ve been asking many Cubans two simple questions: what is the best thing, and worst thing, about living in Cuba? The answer the first part sometimes varies: free health care, the warmth of the people, community spirit, free education, safety on the streets. But the answer to the second question is always the same, whether I ask doctors, students, mechanics or guides: the blockade. Nothing can improve with the blockade in place; the country is stuck on second base.

In the United States, we talk about a trickle-down economy: if the rich get richer, the poor will somehow do a little better. The Cuban view is different. If the blockade is lifted, everyone will benefit equally. What belongs to the state, belongs to the people.

It will be interesting to see how that plays out. Viewed from this perspective, the blockade appears as what it is: a stale, frozen vestige of the Cold War, arrogantly and stubbornly imposed by one country and one country only. Note to the United States: Get over it. End the blockade, and get in the game. Otherwise—to put it plainly—the view from Key West will eventually be a Cuban coastline bristling with Chinese factories, refineries, and God knows what else.

*† *† *

I’m writing this in Cienfuegos, the “Pearl of the South,” a small and very pretty city with French colonial roots and a big, zocalo-like plaza dedicated to poet/freedom fighter José Marti. Another hero here is musician Benny Moré, who famously declared Cienfuegos his favorite city in Cuba.

There are many lovely home stays in this town, and a great theater called the Teatro Tomás Terry (maybe the best-named theater in the world). I’m fortunate to have landed at the Casa Armistad, owned and managed by the now-legendary Armando and Leanor, who have been inviting visitors into their home since the mid-1990’s.

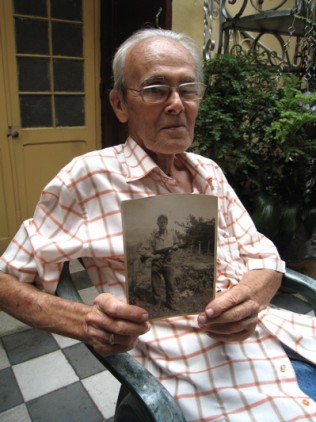

Armando, 73, is fluent in both English and Socialism. To answer my two-pronged Cuba question, he paraphrased a line from Marti: “The sun has spots,” he said, “but ungrateful people see only the spots, and not the light.” When I asked where he was during the Revolucion, he showed me an old photo of himself in 1962, toting a rifle. Then 24, he fought at the Bay of Pigs invasion.

“Since the revolution,” he told me earnestly, “we have never put fire to one American flag. That’s because, in Cuba, we understand the difference between people and their government. To burn your flag would be to disrespect your country, and its people.”

“But I know the two systems,” he assured me, “and I prefer this one.”

When Armando heard where I was going this morning, he gave me a small medallion of Ché. It showed El Comandante looking skyward, the famous pose captured by photographer Alberto Korda. I thanked him for the gift, and turned to Leanor. “In America,” I told her, “many college students have this picture on their dormitory walls.”

“Yes,” she nodded. “I know. Ché belongs to the world. But Fidel?” She grinned, a radiant smile I’ve seen many times these past two days. “Fidel is for us.”

Cryptic, perhaps. Intuitively, though, I know what she means.

Read Ethical Traveler's Reprint Policy.