COLOMBO, SRI LANKA — It’s 6 a.m. on January 24th. The streets are pitch black. Dwayne and I — in the care of a remarkably fluent and urbane driver named Dilan (“Like Bob… or Matt”) — hit the road early, hoping to avoid Colombo’s hellish traffic. We’re heading 75 miles east, to Sri Lanka’s 16th century capital: a beautiful hill town called Kandy.

I’ve been obsessed with making this pilgrimage after my visit, a seeming eternity ago, to the southwestern beaches of Koggala (see my 2nd dispatch). During that trip, the stilt fishermen told me they survived the tsunami because it was a poya, or full-moon day. Full moons are sacred in Sri Lanka; legend holds that Lord Buddha’s birth, enlightenment, and passing to nirvana (extinction from the wheel of life and its suffering) occurred on full moons. Poya days are a monthly Sabbath. Shops are closed, alcohol is not served, and killing — including fishing — is forbidden. It follows that today, the first full moon following the earthquake and tsunami, will be a day of note at Sri Lanka’s main Buddhist shrines.

Last week Dwayne and I visited the ancient city of Anuradhapura, famous for Sri Maha Bodhi: a full-grown ficus religiosa planted from a sapling of the tree that sheltered Buddha during his enlightenment. Kandy has a very different attraction. Two and a half millennia ago, an incisor was recovered from the ashes of the Buddha’s cremation. That tooth now rests in Kandy’s Sri Dalada Maligawa: The Temple of the Tooth. A relic beyond price, it is locked within a series of seven solid gold and jewel-encrusted caskets. No one sees the tooth itself. Even the elite have only glimpsed the seventh, innermost chamber: a small, jewel-encrusted cylinder. (Once a year, in August, the entire reliquary is placed on the back of a gorgeously costumed elephant, and paraded around the Temple grounds with giddy fanfare.)

The number seven is a meaningful digit in Buddhism. The infant Siddhartha took seven steps after his birth, and meditated under the Bodhi tree for seven weeks. Our visit, then, is coincidentally timed. As we arrive at the city’s artificial lake, Dilan explains that exactly seven years ago — on January 25th, 1998, at 6 a.m. — a truck carrying 250 kg of explosives drove up to the entrance of the Tooth Temple. The bomb was ignited — killing at least 20 people, collapsing walls, and shattering the stained-glass windows in a Christian church a quarter mile away.

The psychotic attack (I remember being stunned by the headline) was staged by the Tamil Tigers, in an attempt to destroy the tooth itself. The Temple’s huge iron doors prevented this, but the Temple edifice sustained enormous damage. Now the repaired structure is surrounded by a spiked fence, while police and Sri Lanka Army troops patrol the area day and night.

* * *

Buddhism is a beautiful religion, based on the values of personal awakening and universal responsibility. Buddha’s main teaching centers on impermanence; the undeniable observation that all phenomenon are subject to dissolution. Nothing, in other words, lasts forever. It seems useful, on this full-moon anniversary of the tsunami, to take a break from my Mercy Corps duties and investigate how Sri Lanka’s Buddhist majority (74% of the population) is dealing with the disaster, on both the practical and spiritual levels.

The Kandy sanga, or Buddhist community, is divided into two chapters. One, the Malwata, oversees a quiet and peaceful monastery on the eastern shore of the lake. The other, Asgiriya, has offices in the Tooth Temple itself.

Our first stop is the Malwata complex, where we wait quietly in a cool anteroom for the head monk to receive us. The room is lovely: worn, polished teak floors, with a breeze blowing through the doorway. The skylights are open to the sun, rain and wind. Portraits of smiling monks, all holding round palm fans, gaze from the walls.

While we relax, Dilan (who is from Kandy) tells us that the monk we hope to see — Thibbotuwawe Sri Sumangala — did something rather extraordinary, given the events of 1998. Four days after the tsunami, he and his monks loaded 26 trucks full of food, medicine, and supplies. They drove the trucks due east, and delivered the supplies directly into the hands of the Tamils near Trincomalee.

“It was a way of saying that religion doesn’t matter,” explains Dilan. “For the past 20 years, Sinhalese and Tamils can’t find a chance to talk to each other. With this disaster, there is an opening to communicate — so we give help to them, from the bottom of our hearts.”

Time passes. Dwayne and I wait … and wait. After two hours, we’re told that Sri Sumangala is indisposed, and won’t be able to meet us. Normally, such a turn of events would twist my mindset into a balloon hat. But after our long rest amid so many enlightened faces, I simply wag my head and fetch my flip-flops.

* * *

The Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic of Lord Buddha, as it’s formally known, is an opulent place, with numerous chambers, ante-chambers, balconies, libraries, altar rooms, and inner sanctums. During our visit the inner courtyard is decked with thousands of flowers, and jammed with devotees. Everyone is wearing white. Strings of gardenias surround the inner chambers, and incense burns everywhere. The smells and hubbub are intoxicating. (You don’t meet a lot of South Asians, we note, lobbying for “fragrance-free” environments.)

Dilan leads us out of the main temple and through a side door, avoiding the crowds craning for a glimpse through the opened door of the Tooth chamber. We cross a grassy yard where people light oil lamps in wrought-iron candelabras shaped like Bodhi tree leaves and eight-spoked wheels (a symbol of Buddhas “Eightfold Path” to liberation). Yesterday, we learn, 20,000 lamps burned in this courtyard — a luminous memorial to the tsunami victims.

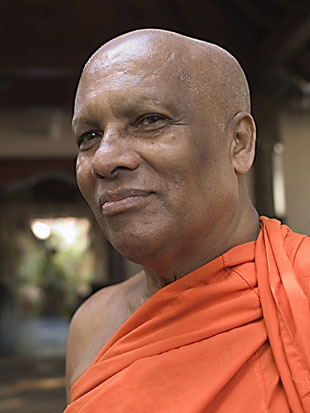

To our right is a garden compound, removed from the bustle of the temple itself. Here, in a dark and cool room decorated with pictures of past Asgiriya abbots, we find the Tooth Temple’s Chief Monk. His name is also a mouthful: Reverend Warakawe Dhammaloka Thero.

Dhammaloka is one of those monks one loves at first sight. He’s a broad shouldered man in a bright orange robe, affable and perpetually amused. Dilan, who will translate for us, bows low, placing his hands together in respect. We follow suit.

“I’ve just returned from Colombo,” Dhammaloka, who is also a professor at the University of Peradeniya, states cheerfully. “And I was about to take a nap, and prepare for this evening’s rituals. But so many of you, from around the world, have given our country so much. My time is yours.”

My first query for the Reverend is this: How do you, as a Buddhist leader, counsel people who have lost so much in this disaster? What lesson can be learned from this event?

The answer is complex but sensible. Immediately after the tsunami the monks began a series of chanted blessings, performed every evening since. But that, Dhammaloka explains, “is like aspirin.” The next pressing need is food and shelter. On February 4th the prayers will end, and the monastery will concentrate on direct relief. And while the monks assist the refugees materially, they will work with their minds as well.

“We’ll try to explain to the people,” Dhammaloka says, “the impersonal nature of the event. This is the reality of karma. Our life doesn’t belong to us; it’s like a flame that can be extinguished in an instant, without warning.”

There are two important terms in Buddhism, explains Dhammaloka, that relate to the tsunami. One is kalachakra, the Wheel of Time. The other is kalavipati: the naturally occurring disasters that occur on that Wheel. No one expects terrible things to happen; but good and bad events are inevitable facets of human life.

“The is the real medicine,” Dhammaloka explains. “But it’s not easily absorbed. It takes a long time to work.”

I have one more question: What is the main challenge for the monastery, and the Buddhist community, during the coming year? Dhammaloka nods, then points to my notebook, indicating that his next statement, more than anything, must be recorded.

“At this time,” he says, “so many countries have stepped forward, offering to help Sri Lanka and asking nothing in return. The government must learn to organize these people, and help them work together as a single team. Otherwise, there is only inequality, confusion, and resentment. In that case, the tsunami disaster will be never-ending; like a wound that never heals.”

As I rise to go, the monk asks me to write down one final thing. “Please,” he says. Make a special note. To everyone who has helped us, from any country, of any religion, of any age. As one human being to another: thank you.”

We leave the shade of the garden, emerging into the clouded dusk of the temple grounds. Fruit bats sail through the sky. Beneath a huge open-air shelter, thousands of devotees — housewives and teachers, taxi drivers and lawyers — chant prayers of salvation. Oil lamps flicker, and the full moon rises behind the Kandy hills.

Wednesday, January 26th, is the one month anniversary of the tsunami. Dwayne has flown back to San Francisco; I’ve returned to Colombo. At 8:30 in the morning, Dilan turns on the car radio and combs the airwaves. Beginning at 9:05, he informs me, services will be held for the souls who perished in the waves. Four events — one for each of the main religions — are scheduled at four locations, across the breadth of this battered island.

In the Nallur temple in Jaffna, far to the north, Hindus are performing pujas for the dead. The Kandy temple is hosting yet another invocation, and the Madu church, in Puttalam, is conducting Catholic rites.

Here in Colombo, the place to be is the Devatagaha Mosque: an elegant white building, flanked by minarets. Sri Lanka’s population is only 10% Muslim, but many of the affected people were Islamic fishermen. One of the first people I meet inside the spare, echoic mosque is Naqeeb Mowiana, a lanky, friendly man in a tight skullcap. “From Galle to Hambantota,” he tells me, “my father’s family lost 37 people.”

I’ve brought no skullcap, but the groundskeeper improvises. A small plastic fruit basket is overturned, and placed on my head. Sporting this ridiculous attire, I am ushered into an office to sit with the visiting dignitaries. “We are praying to The Almighty,” I’m told by the deputy mayor of Colombo, “to let the victims of the tsunami enter Jennathul Firdhouse; the Gardens of Paradise.”

It amazes me that the place isn’t filled with media. In fact, I’m the only foreigner present. Not only that; I’m American, and Jewish. As this information circulates, it becomes clear, to the assembled believers and this infidel alike, that my presence here cannot be accidental.

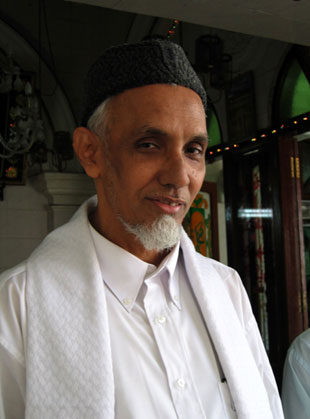

At 9:05 a.m., the time of the first wave, fifty men in spotless caftans and skullcaps gather in the mosque’s prayer-room. Led by their Imam — the fiercely dynamic Jaleel Muhiyaddeen Qadirie, considered by his followers a living saint — the chanting begins. Standing amid these men, in a white-tiled room with fans whirling above and pictures of Mecca on the walls, I lose all sense of national and ethnic boundaries. The oration is in Arabic, and the only word I understand is “tsunami.” But the passion in Qadirie’s voice is universal.

The prayers continue until 9:36 a.m. — the moment the great wave impacted the shores of Sri Lanka, sweeping more than 30,000 people to their deaths. Interspersed throughout is the Imam’s sermon: a call for all the residents of the land to join together, and rebuild Sri Lanka.

“Some of those who went to their morning prayers on that day,” the Imam cries, “did not pray in the afternoon. This is the lesson for everyone. The tsunami picked up everything, and everyone; it called each person by name, deciding whether they would live or die. Regardless of who you are, there is no guarantee of a second day, or hour, or even a second breath. Yesterday is gone; tomorrow is doubtful. We have only the present moment to do good works, to love each other, and to praise God.”

There is a prayer that the people of Sri Lanka learn to live together peacefully, and a prayer of thanks for the agencies and charities that have come to the county in its hour of need. Chants of amin, “may it be so,” follow each benediction. Around me, the men place their palms upward in supplication, or over their hearts.

When the ceremony concludes, the circle of worshippers begins to rotate, forming a receiving line that snakes past the Imam and other VIPs. Everyone shakes each other’s hand, and murmurs of greeting and blessing ring through the tiled room. All this is being filmed; and I try, discretely, to back away, feeling out of place among this community of worshippers. But I’m taken by the arm, and pulled into the fray by an elderly man who reminds me of my grandfather.

“You must come,” he says, simply. “You, and I; same God. All, same God.”

I enter the circle, and move with the crowd. One by one, in turn, each man takes my hand. Every one of them looks directly into my eyes, with an expression I cannot describe and will never forget. I’m thinking: No soccer ball or Frisbee, no tarpaulin or school book, has meant more to these people than my presence in this room. And nothing I’ve accomplished with Mercy Corps, as part of their relief effort in Sri Lanka, has meant more to me personally.

Later, after a cup of milk tea in the mosque office, the Imam approaches me. “Are your parents alive?” he asks.

“My mother is alive,” I reply. “My father passed away 20 years ago.”

Jaleel Muhiyaddeen Qadirie, tsunami survivor and servant of Allah, reaches into his breast pocket and extracts a crisp 1,000 rupee bill. He places it in my hands, and holds it there.

“When you return home,” the Imam says. “Buy your mother a bowl of fresh fruit.”

As we leave the mosque and reclaim our shoes, I query Dilan. “Do you understand why he did that?”

“Of course,” my guide replies. “He is Muslim. Very generous people. And by the way…”

“Yes?”

“Your own fruit bowl is still on your head.”

* * *

I spend the hot afternoon indoors, writing up my notes. By the time I leave my room it’s half past six. I walk slowly along the seaside promenade of Galle Face Road, and buy 20 rupees worth of potato chips from a street vendor. The bag is homemade, folded from a page cut from an old science textbook: an illustration of the lunar module, en route to the Moon.

Sunset comes quickly near the fast-moving equator. The Arabian Sea fills the western horizon, pink-tinged gray from north to south. A few weeks ago, people walked along this beach in silence, staring fearfully at the swell. The healing process is well underway, but one wonders if the lessons have been learned — and not just in South Asia.

“You can read a thousand books,” the monk in Kandy told the assembled crowd, “but if you don’t apply them to your life, you haven’t learned anything. In the same way, if mankind ignores nature, and the language of nature, we will always be caught unawares. The sea warned us, when it pulled away from the shore; many people treated it like a curiosity. Many who were warned thought it was a joke. Those who understood, survived. Those who didn’t, perished.”

I munch a few chips and look west, toward the tankers on the horizon. Below, along the breakwater, the surf slaps the shore with a steady, gentle rhythm. Couples and children frolic on the sand, gleefully dodging the waves.

Read Ethical Traveler's Reprint Policy.